A new book explores Antonio Bonet’s grand plans for Buenos Aires public housing

[ad_1]

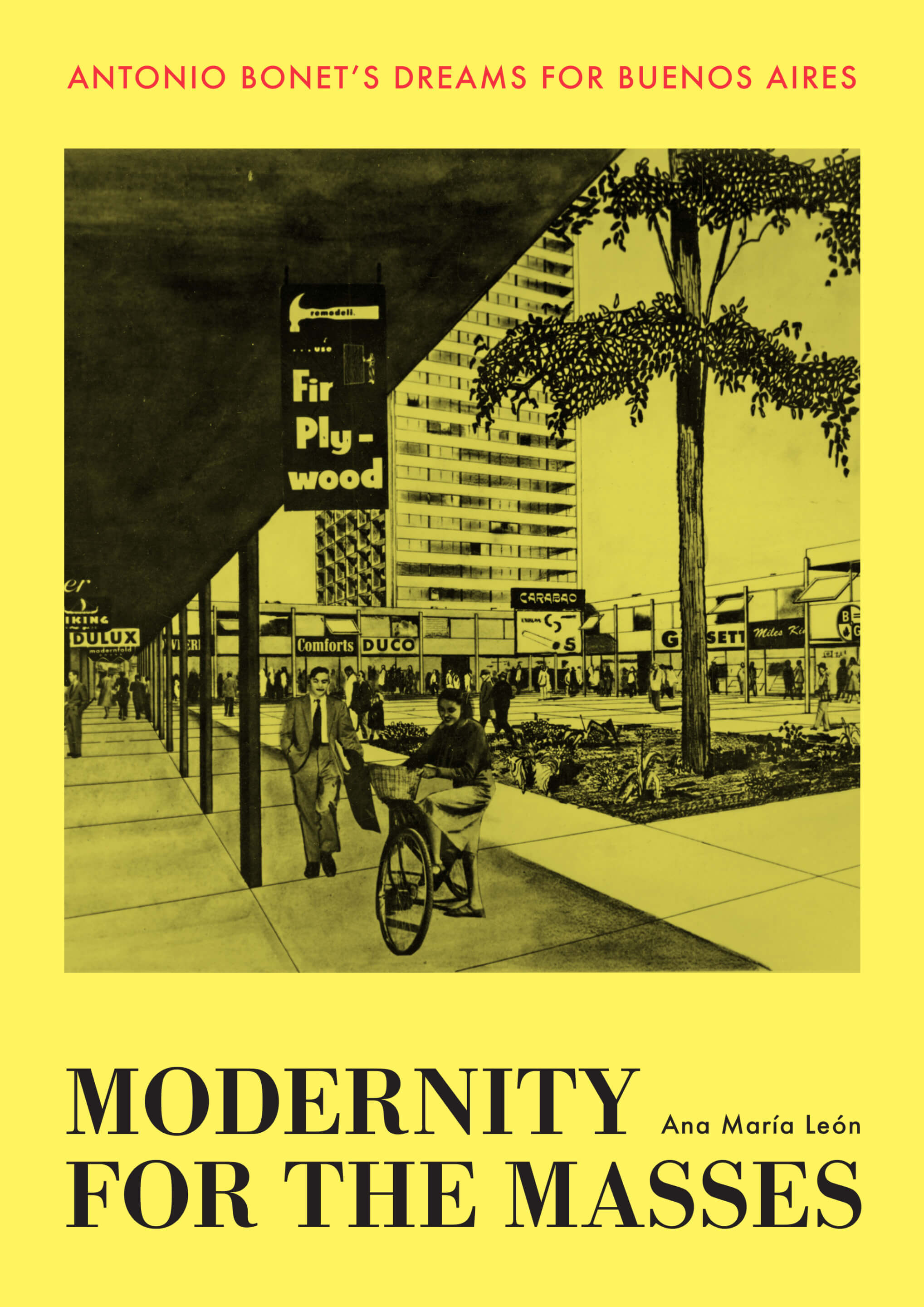

Modernity for the Masses: Antonio Bonet’s Dreams for Buenos Aires

By Ana María León | College of Texas Press | $50

Open up Ana María León’s Modernity for the Masses: Antonio Bonet’s Dreams for Buenos Aires and you’re as likely to face collages by German Argentine photographer Grete Stern or an abbreviated heritage of psychoanalysis in midcentury Argentina as you are to locate nearly anything about the book’s subtitular character. We can examine a great deal of a country’s history by way of its buildings and a great deal about a male as a result of his pathologies, León looks to say, but we also need to know when and how to glance elsewhere. Although Modernity for the Masses is in fact anchored by Bonet’s architectural layouts, León is careful to paint a full photograph of the large, sophisticated cultural and political context from which they emerged.

Born in Barcelona in 1913, Antoni Bonet i Castellana belonged to a era of cultural avant-gardists in Europe who thought the Americas to be a kind of tabula rasa. Architects of Bonet’s stripe saw the Western Hemisphere as providing much more favorable disorders for follow: In 1938, he wrote to a colleague, “I want to get started setting up, and you know right here there is nothing at all to do.” Buenos Aires had the added edge of currently being culturally and climatically very similar to Barcelona, and for that reason was a area wherever he could sense almost at dwelling. Off he went across the Atlantic.

León sets up this story deftly: Instead of commencing with Bonet, she commences with Buenos Aires. Modernity for the Masses opens with an graphic of people—union customers, protesters, youthful men—standing in a public fountain and calling for the liberating of Juan Domingo Perón, the temporarily embarrassed, imprisoned basic who would later become president. The scene is 1 of political unrest and unknowability. León cites a newspaper headline that likens the protesters to cattle, as if the rural Argentine Pampas experienced invaded the burgeoning metropolis. She provides us the massive photograph, then Bonet storms in, grand ideas in tow.

Grand plans for general public housing, to be specific. As emigration from Europe and migration from the countryside into Buenos Aires swelled, throngs of persons required locations to reside. For the city’s ruling class, the masses were also a very well of innovative potential. Elite tension to tame these unruly brokers would occur to notify all Bonet’s public commissions, which, mainly because they have been meant to be financed by the condition, catered to its political desires. León examines 3 housing strategies that were created at radically diverse moments in modern day Argentine background and, consequently, different significantly in their political motivations, aims, and supreme effects. While she closely examines the architectural sort of each individual plan, Léon is more intrigued in the image—of a region, of a metropolis, of a certain established of politics—the assignments instrumentalized, and how Bonet, and his vanguard architecture team Austral, participated in that system.

Choose Casa Amarilla, a task in the La Boca community developed in the course of the conservative military dictatorship that lasted from 1943 to 1946. Architecturally, it adopted the tenets of CIAM, while also making on other cultural currents that linked the porteño intelligentsia to European metropoles, significantly Barcelona and Paris. (Bonet had lived in the French money operating for Le Corbusier just before leaving the continent.) In accordance to León, with Casa Amarilla “social housing and the masses it was intended to include were being elevated to a monumental scale through a sculptural form that was basically lifted higher than its environment.” Maps and architectural drawings reveal an just about grotesque monumentality, which, León notes, belied a additional cynical purpose: not to elevate the masses but, alternatively, to control them.

Modernity for the Masses is instructive in the way it evidently distinguishes between architectural aspirations and the real (or possible) influence a setting up has in the earth. With a keen, skeptical eye, León displays what comes of kind when it mixes with structural and systemic forces. Try out as architects could possibly, they will in no way management the circumstances in which their designs are created, nor individuals by which their creations are gained.

The narrative carries on with a pair of megalomaniacal assignments, Bajo Belgrano (1948–49) and Barrio Sur (1956). They had been variants on Bonet’s strategies for La Boca, only the scope experienced expanded his architecture would project a clear, “civilized” modernity on to Buenos Aires much more broadly. As a eyesight assertion for Perón’s populist reign, Bajo Belgrano, with its orderly system and immaculate plazas, represented a marked upgrade from the shabby general public housing in which a lot of working-class men and women experienced lived. Barrio Sur, built through the tenure of the reactionary army routine that overthrew Perón a second time (both equally resilient and corrupt, he emerged for a 3rd presidential phrase in the 1970s), utilized the same official orderliness but to distinctive ends—not to household the operating course but to displace them, to rid the town of their presence. “Antiseptic top quality is introduced as civic virtue,” León recounts.

Irrespective of his avant-garde bona fides, Bonet, it appears, was agnostic as to who would in the end fund his initiatives. At a 1975 convention in Santiago de Compostela, he blamed his lackluster setting up streak on the political “instability” of his adopted homeland, somewhat than any distinct set of policies. Argentina, he reported, experienced forfeited “its superior position to Latin America” to Mexico and specially Brazil, “whose political stability, both of those in the democratic routine and for the duration of the dictatorship, has been noteworthy.” Brasília, instead of Buenos Aires, showed the way forward.

In Bonet’s arms, the exact same architectural concepts, the very same grand visions, could be applied to appease and satisfy any pursuits, from these of a populist authorities to those people of a appropriate-wing dictatorship. He was not the 1st architect to indiscriminately peddle his products and services (Mies could count communists, fascists, and capitalists as clients), nor was he the very last (keep in mind Bjarke Ingels assembly with Bolsonaro?). But as explained to by León, Bonet’s tale serves as a key example of the political malleability of avant-garde aesthetic concepts and of the certain susceptibility of architecture to staying co-opted by political agendas. She tends to make obvious that architecture, a lot more than any other artwork, wants ability to enact it.

In the end, none of Bonet’s jobs for Buenos Aires were being at any time developed. Simply call it bad luck, very poor timing, or something else. I phone it a reminder that when it arrives to building for the masses, we want less grand visions and a lot more political will.

Marianela D’Aprile is a writer dwelling in Brooklyn. Her perform on architecture, politics, and culture has appeared in Metropolis, Jacobin, ICON, The Country, and elsewhere. She sits on the board of The Architecture Lobby and is a member of the Democratic Socialists of The usa.

[ad_2]

Supply website link