Brooklyn Reimagined with Heritage Reuse and Innovation Centric Mixed-Use Campus by Industry City – Cornell Real Estate Review

[ad_1]

Project Background and Site Summary

The waterfront-bound neighborhood of Sunset Park lies between Gowanus and Bay Ridge, spanning between 15th street to 65th street between 9th Avenue across the 8th avenue corridor. Industry City is a new mixed-use development set on 35 acres of centuries-old industrial land in Sunset Park. It is one out of three massive historical industrial complexes along the Brooklyn Waterfront. One of them being the Brooklyn Navy Yard, where the CEO of Industry City, Andrew Kimball led the transformation of the 300-acres former Naval ship-building facility. The other one is the Brooklyn Army Terminal on 65th street from where troops shipped out during the World War I and World War II. The third one is the Bush Terminal, which is where Industry City exists today, and it used to be the port for manufacturing goods coming in and being warehoused for further distribution in New York City. All three developments experienced peak employment between the years 1930-1960 but hit a long period of disrepair in the 1970s when large scale manufacturing shifted to other US cities. The Brooklyn Navy yard and the Brooklyn Army Terminal being publicly owned were quickly brought back to life through massive subsidies provided by the government to fix the decades of deferred maintenance.

The Brooklyn Navy Yard is a leading model for industrial heritage reuse that under the leadership of Andrew Kimball took $280 Mn from the City of New York for basic infrastructure improvements and leveraged $1 bn of private investments to create thousands of innovation economy jobs.[1] It was in August 2013 when Mr. Kimball joined Industry City to direct the redevelopment of the long-underutilized privately owned industrial facility. At present, the 6 million sq.ft. of mixed-use space is designed as a creative hub to attract retail and commercial tenants from across the different boroughs of Brooklyn. Industry city is co-owned by Jamestown Properties, Belvedere Capital, Angelo Gordon & Co., Cammedy’s International and FBE Limited. Jamestown Properties which is a design-focused real estate investment and management company is the brainchild behind the vision and the leasing strategy of Industry City having executed iconic projects such as Chelsea Market in New York City and Ghirardelli Square in San Francisco. The main challenge at hand for Industry City has been to take a massively privately owned site without government relief to structure the ecosystem of uses that will drive the creation of private investments. The vision revolves around industrial heritage reuse while keeping innovation economy principles at the forefront. This translates into place making for modern manufacturing standards that is not simply about making physical products but facilitating a new kind of manufacturing at the intersection of design, art, technology, and engineering. The 5000 sq.ft. of space earlier required to assemble segregated parts in a single product can be achieved in a 500 sq. ft of space using technologies such as 3-D printers and laser cutters.

Jim Somoza, Managing Director at Industry City referred to a “campus vision”, with the entire development divided into 16 office buildings and the ground floors of each building connected via a seamless hallway while standing at one of the former train platforms used for industrial transportation during a ULI NYC site tour. Each building has unique characteristics embedded in its design, tenants, and waterfront view. Mr. Somoza explained how this adaptive reuse project was not simply about repurposing an old industrial development into office space but intended to retain the character of the neighborhood while bringing vibrancy and connectivity. The remains of the railway tracks from the former “Bush Terminal” are noticeable, reinforcing the site’s historical significance and the harmonious placement of the interactive outdoor art installations such as the “Pool” by Jen Lewin. The project includes $125 Mn[1] in capital investments by owners over the span of 10 years and a recent stake purchased by a Singapore sovereign-wealth fund GIC Pte. Ltd. that put a valuation of $1.3 bn on the sprawling Industry city project as of end of 2020.[2]

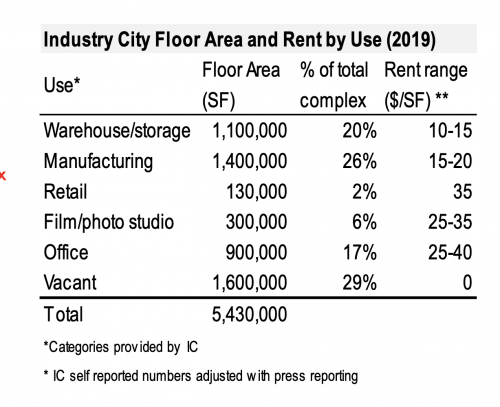

Here at Industry City, the developers have adapted the “shared office” model for the office tenants spread across 600,000 sq.ft. of total campus area, alongside a coworking space of 30,000 sq.ft. When marketing the property, the team knew that they weren’t seeking traditional Finance, Insurance, Real Estate (FIRE) tenants who would typically pick a traditional Manhattan office space. They worked to attract firms focused on design, architecture, marketing, fashion, consulting, technology, equipment supply, and other creative fields. The focus from the very start has been on building a community and providing a creative space for innovation. The retail portion makes up about 1 million sq.ft. of the total space with the leasing strategy of “local yet global” users.

The restaurant offerings are unique and unknown. They are not the go-to outlets plucked from Manhattan and transported into Sunset Park. They are mostly independently run mom-and-pop shops from across the country and with diverse backgrounds. One highlight includes a Californian couple who invested their life savings to bring Korean comfort food to Brooklyn at Ejen. The developers placed special interest in the success of the vendors, especially during the pandemic. They were able to retain all but one tenant post-March 2020 by providing reasonable concessions. The vendors returned more resilient and built a community around this shared resilience. An optimal retail strategy has been leasing out wholesale space for vendors like Lilac Chocolate and Colson Bakery, to supplement their retail stores right next door. This way the vendors can showcase the development cycle of their products while delivering it fresh to customers. The developers applied a countercyclical approach to attracting office and retail tenants. Colson Bakery has always operated as a local wholesaler, supplying baked goods across Brooklyn and Manhattan. Jamestown placed Colson Bakery at a central location and assisted them in launching a retail business arm, transforming them into an anchor tenant. The Colson Bakery team initially resisted opening a retail location but has since accrued great margins and is considering further expanding the business. As foot traffic increased from the office tenants, more established local brands such as Sahadi’s and Frying Pan opened shop in Industry City.

Post-Covid, 60-70% of the office tenants at Industry City have returned, as compared to a 20% rate for Manhattan companies. This has helped maintain foot traffic of 12,000 per day on the weekdays, of which 16% are visitors and 84% are employees, and 9,500 per day on the weekends, out of which 84% are visitors and the rest are employees.

It is essential to note that the Industry City project is not a copy-paste version of the Chelsea Market business model. The Industry City model is based heavily on the community and has a destination-oriented approach. It is not seeking international tourists but local New Yorkers who are curious about exploring different New York neighborhoods. Mr. Somoza likes to say their business is transportation, not real estate, in the sense that his team worked hard to curate tenants and develop a design strategy that transports visitors to global destinations. The Japanese Market is an open supermarket where one can watch a blacksmith while shopping for fresh, local sashimi. There is an upcoming one-of-a-kind Mexican market owned and operated by a Mexican native in the development. Industry City is the culmination of ideas, design, and quality while retaining the rough edges of the industrial aspects of the development.

Community buy-in was critical from the very start of the project, as the developers sought to revitalize the Sunset Park waterfront area, which has experienced poverty, blight, and a historic lack of investment. The support from local government and community members was key in obtaining tax credits for the brownfield redevelopment.

Potential Setbacks

Beginning in the 1950s, Brooklyn waterfront industrial developments experienced a general abandonment of vertical urban industrial properties due to a drastically changing manufacturing landscape. By the 2000s, the employment base around Industry City had dropped by 60 percent and much of the warehouse and office spaces were underutilized. Despite the deteriorating conditions of the neighborhood, in 1986 the nation’s first Chinese American supermarket called “Winley Supermarket” opened on 8th Avenue and 56th Street. This marked the onset of the growth of Sunset Park’s Chinatown, which does not experience the tourism of Manhattan’s Chinatown. The second-largest ethnic group of the neighborhood can be found northeast of 8th Avenue, composed of Latinx first-generation family homes, Mexican American core businesses, and family-run restaurants. According to the 2010 U.S. Census, nearly half of Sunset Park’s residents are foreign-born and about 51% live in rent-controlled apartments.

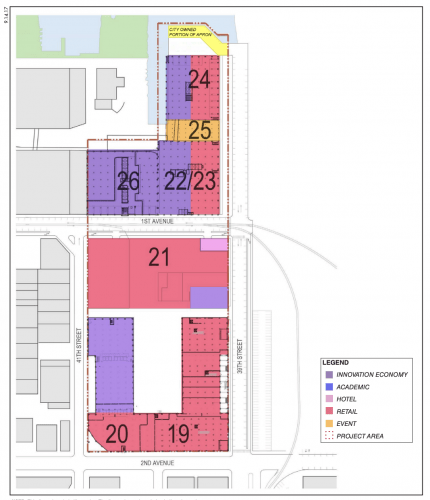

The ambitious plan by Industry City to revitalize the Brooklyn waterfront is accompanied by potential gentrification and a lack of social equity responses to address resulting negative impacts, such as real estate pressures, rent increases, and reduced affordability. In early 2020, Industry City put forward a rezoning application called “The Sunset Park Waterfront Vision Plan 2020” to rezone a portion of the affected area from an M3-1 zoning district to an M2-4 zoning district to expand the existing Industry City campus development. The company contended that the existing zoning from 1985 required revision and rezoning would remove the outdated restrictions, such as square footage cap requirements for retail developments or changing the Floor Area Ratio (FAR) from 2 to 5.[1] The overarching themes included rehabilitated empty spaces through adaptive re-use strategies that would double as waterfront resiliency zones and place the neighborhood on the map for technology companies and developers. According to Startup Genome, a leading innovation and research firm, the growth rate of startups in Brooklyn is higher than in any other city in the United States, except for San Francisco.[2]

Despite the argument for turning the dilapidated industrial complex into an innovation-centric employment hub, the NYC City Council rejected the rezoning proposal as community members and city council officials opposed expanding Industry City by building high-end luxury housing units and hotels. Groups Protect Sunset Park and UPRISE rallied against the plan, stating how the negative implications of the proposal would supersede the job creation prospect by fueling gentrification in a community with a critical shortage of affordable housing.[3]

This brings attention to the critical problem of how to effectively uplift a local community while being mindful of the resulting social inequity. The concept of an innovative economy is essential to the development of an innovation district, and is created through Disneyfication, which is the transformation of an underutilized community into a controlled and safe environment. Industry City aims to respect the historical aspect of its campus by repurposing the socio-economic structures into a unique, cultural, and vibrant frontier. However, this Disneyfication comes with a cost of potential gentrification.

On the other hand, Industry City still faces leasing pressures with the neighborhood of Sunset Park in dire need of infrastructure improvements and increased safety requirements, especially following the recent subway shooting incident at Brooklyn’s 36th street subway station in which 23 people were wounded following violent gunfire.[4] To attract long-term tenants and local visitors, the government needs to support local businesses and large-scale developments to attract private investments and encourage public-private partnerships.

Impact Assessment

Of great importance to the Industry City project’s success has been the community’s commitment to uplift residents and the neighborhood’s empowering progress in overcoming a history of underdevelopment and underinvestment. This has helped in securing the required funding, approval process, and engaging well-known developers, architects, and urban planners. Revitalization development projects in distressed neighborhoods can largely benefit from public support. Public incentive funding and creative financing measures are important financial sources, especially in public-private jointly executed projects like Industry City. Even though Industry City is likely to increase gentrification, it is more likely to put in place a revenue-generating, safe environment, essential for the continued development of the neighborhood.

References:

[1] La Porte, Kimberly, “The Brooklyn Navy Yard: A Mission-Oriented Model of Industrial Heritage Reuse” (2020). Theses (Historic Preservation). 691

[2] Chan, Stephanie Yee-Kay. “Innovation, Intention and Inequities: Addressing the Potential Social Impacts of Innovation Districts in Post-Industrial Waterfront Zones upon Working Class and Minority Neighborhoods.” Columbia University, 1 May 2018.

[3] Grant, Peter. “Singapore’s Gic Buys Stake in Brooklyn’s Industry City.” The Wall Street Journal, Dow Jones & Company, 12 Feb. 2020

[4] “Industry City.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 19 Dec. 2021.

[5] Menchaca, Carlos. New York City Council Member- District 38.

[6] Startup Genome. “Top Global Ecosystems – Best Startup Cities – Startups Rankings.” Startup Genome,

[7] Spivack, Caroline. “The Industry City Megadevelopment That Wasn’t, and How the Deal Fell Apart.” Curbed, Curbed, 23 Sept. 2020.

[8] “Police Arrest Suspect in New York Subway Shooting ‘without Incident’.” BBC News, BBC, 14 Apr. 2022.

[9] Chan, Stephanie Yee-Kay. “Innovation, Intention and Inequities: Addressing the Potential Social Impacts of Innovation Districts in Post-Industrial Waterfront Zones upon Working Class and Minority Neighborhoods.” Columbia University, 1 May 2018.

[10] Menchaca, Carlos. New York City Council Member- District 38.

[ad_2]

Source link